Postpartum pain is common. All women experience uterine cramping in the early postpartum period that is necessary to prevent excess bleeding, and women with lacerations from vaginal birth experience perineal pain. After cesarean birth, women experience pain from the laparotomy. It is necessary to treat pain adequately to support maternal comfort and to reduce the stress response of the mother and newborn. It is also critically important to limit the amount of opioids prescribed on discharge that may lead to prolonged use and possibly misuse. Leftover medication is a common source of opioids that are diverted for misuse. The potential for diversion and misuse of opioids make it a public health priority to prescribe only the minimum amount required by the patient.

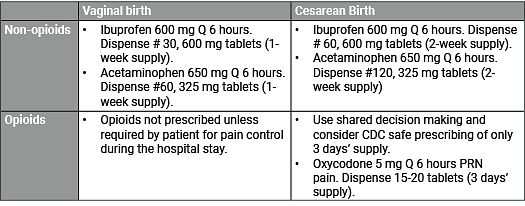

Cesarean birth is the most commonly performed surgery in the United States, yet little is known about appropriate pain management at discharge. In general, women consume half the amount of opioids prescribed to them on discharge. For example, a recent study found that the median number of opioid tablets prescribed was 40 and the median consumed was 20 (Bateman BT, et al, 2017). The amount of opioid consumed was directly proportional to the amount prescribed. However, the amount of opioids dispensed did not correlate with patient satisfaction, pain control, or the need to refill the opioid prescription. The majority of women do not require an opioid prescription after vaginal delivery. Despite the well-known risks, 29% of women were prescribed an opioid at the time of discharge after vaginal delivery.

Enhanced Recovery: There is a national effort for all surgeries to redesign care for the peri-operative period to enhance recovery. In May 2019, the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) released a comprehensive set of guidelines (see Resources) for each phase of care for women undergoing a cesarean birth known as Enhanced Recovery After Cesarean (ERAC). Every obstetric unit should strongly consider these recommended approaches. A part of enhanced recovery is optimizing care so that the need for opioid pain medications is markedly lowered and/or replaced by non-opioid approaches. A Call to Action for ERAC with a comprehensive discussion was published in the August 2019 issue of The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. One of the goals is to ensure that all women have access to adequate pain control while reducing the harms of opioid exposure.