Ideally, providers can use MI curricula to become more proficient in these techniques, and all levels of staff can participate in these curricula and employ these techniques. One such curriculum is included in the Resources section for this Best Practice. In the absence of formal training, several specific MI strategies and techniques are described below.

Incorporate the foundational principles of MI into communication with pregnant and parenting women with opioid use disorder (OUD). These foundational principles of MI should be employed continuously over time and include:

- Express empathy through reflective listening

- Develop discrepancy between patient’s goals or values and their current behavior

- Avoid argument and direct confrontation

- Adjust to patient resistance rather than opposing it directly

- Support self-efficacy and optimism

Employ the following general style of MI in all patient communication:

- Asking Permission – Permission is a deeply respectful foundation of mutual dialogue

- Engaging – Engagement is the establishment of trust and a mutually respectful relationship

- Focusing – Focus is the ongoing process of seeking and maintaining a direction for the exploration conversation

- Evoking – Evoking refers to eliciting the patient’s own motivation for change.

- Planning – Planning is the process of deciding on a specific plan for change that the patient agrees is important and is willing to undertake.

- Linear and Iterative Processes – Change talk within MI is both a linear and iterative process.

The following are specific motivational skills and strategies that can be practiced and incorporated into all patient engagements, especially those that involve behavior change and compliance with treatment plans. Each of these strategies is described in more detail in the MI Curriculum included in the Resources section of this Best Practice.

Employ the OARS+ model as one set of specific MI skills.

- Open ended questions elicit crucial information that may not be gathered from close ended questions.

- Instead of asking “Have you used any drugs during your pregnancy?”, one might say “I treat a number of women who have used prescription medications and other drugs during their pregnancy. Please share with me which kinds of prescription meds or other drugs, if any, you have used during or before this pregnancy.”

- Instead of asking “Have you ever been in treatment?”, one could request “Tell me about your recovery journey.”

- Affirmations are statements of appreciation

- “I’m impressed that you followed up with the MAT referral”

- “You’ve stayed off drugs for 2 months. That’s great!”

- Reflections establish understanding of what the patient is thinking and feeling by saying it back to the patient as statements, not questions.

- Patient: “I’ve been this way for so long.”

- Provider reflection: “So this seems normal to you” or “So this seems like a hard cycle to break.”

- Summaries are highlights of the patient’s ambivalence that are slightly longer than brief reflections and serve to ensure understanding and transition from one topic to another.

- For a patient wanting to stop using drugs during pregnancy: “You have several reasons for quitting drugs: You want to get your life back, you want to give your baby the best chance at a healthy life, and you want to be able to manage life’s issues without relying on drugs as a crutch. On the other hand, you’re worried about what kind of recovery path would work for you; you’re worried that you won’t have the motivation and strength to stick with a recovery path. Would that sum it up?”

Rolling with resistance requires the listener/provider to pause and shift conversations when signs of an argument or confrontation begin to appear. Resistance behavior occurs when points of view differ, generally when the provider is moving the patient ahead too quickly, or the provider fails to understand something of importance to the patient. When resistance appears, the listener/provider should change strategies and utilize OARS techniques.

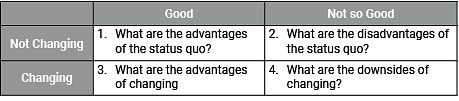

Developing discrepancy involves the listener/provider guiding the conversation so the patient can articulate their personal beliefs and future goals (listen especially for statements about life, family, health, financial status, living situation, and other personal considerations). Developing discrepancy between the patient’s behaviors and their broader life goals is essential because patients are more often motivated to change when they arrive at that conclusion themselves rather than hearing it from someone else.

Change Talk is defined as statements made by the patient that indicate motivation for, consideration of, or commitment to change behavior. There are clear correlations between patients’ change talk and outcomes. Once the listener/provider and patient have established a trusting relationship and have open communication about the patient’s substance use, the listener/provider can guide the patient to expressions of change talk using some of the techniques listed below. Each of these strategies is described in more detail in the Motivational Interviewing Curriculum included in the Resources section of this Best Practice, along with additional strategies for eliciting change talk.

- Preparing change talk employs the DARN model as one set of specific MI skills

- Desire to change (Ask “Why do you want to make this change?”)

- Ability to change (Ask “How might you be able to do it?”)

- Reasons to change (Request “Share one good reason for making this change.”)

- Need to change (Ask “On a scale of 0-10, with 10 being the highest, how important is it for you to make this change?”)

- Implementing change talk employs the CAT model as one set of specific MI skills.

- Commitment (Ask “What do you intend to do?”)

- Activation (Ask “What are you ready (or willing) to do”?)

- Taking steps (Ask “What steps have you already taken?”)

Coding and Reimbursement – MI focused on increasing the patient’s understanding of the impact of their substance use and motivating behavior change can be coded for reimbursement whenever a positive screen (through interview, formal screening tool, or toxicology) is identified and documented in the medical records. Evaluation and Management (E/M) service codes for both assessment and intervention are listed below (and can be coded with modifier 25 when they are performed during the same clinical visit as other E/M services):

- 99408 – Alcohol and/or substance abuse (other than tobacco) structured assessment and brief intervention services 15-30 minutes (the comparable Medicare code is G0396)

- 99409 – Alcohol and/or substance abuse (other than tobacco) structured assessment and brief intervention services greater than 30 minutes (the comparable Medicare code is G0397)