Toxicology testing has a necessary role in the care of women who use substances during pregnancy. The results are useful to encourage dialogue with the patient and can be necessary for clinical decision making. However, the results can also have devastating consequences for the mother and baby when used inappropriately by other agencies and can result in punitive consequences. Furthermore, toxicology results are easily misinterpreted by those who are unfamiliar with the nature and limitations of testing. Limitations of testing include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Many substances may not be detected (false negatives), including synthetic opioids and designer drugs

- Risk of false positives

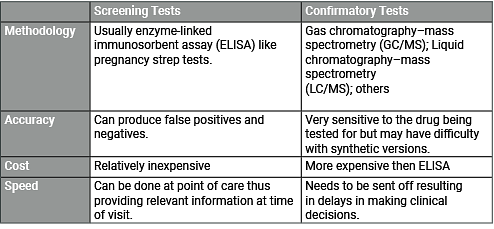

- Need for confirmatory testing for any positive toxicology result

- Testing does not provide information on severity or duration of use

- Testing can only assess for current or recent use

- Even if results are negative, sporadic use is not ruled out

- A positive urine toxicology does not confirm a substance use disorder (SUD) any more than a negative result rules it out

The evidence suggests that hospital staff are more likely to perceive Black women as being at higher risk of using drugs, even though white women have similar rates of illicit drug use. Black women are therefore more likely to be tested, and more likely than white women to face punitive consequences such as having their children placed in protective care.

Even objective medical criteria for determining who should have toxicology testing may be subject to inadvertent bias. For example, “inadequate prenatal care” is a common, and often necessary, criterion for toxicology testing. If this criterion is used as a prompt for toxicology, providers and nurses must understand that a variety of factors other than substance use may influence whether a woman can remain in care, including lack of insurance, inability to take time off of work, and lack of culturally appropriate care. All these factors are more likely to impact poor women and women of color.